A Case Study for the Laocoon:

The Integration of the Arts and Humanities

|

|

Karen T. Moore, Grace Academy, TX

The students look at such art illustrating their textbooks or classroom walls, but how often do they see past the surface? Our fine arts teachers train them to admire the technical skill of the artist: smooth lines, scintillating curves, the delicate features, the way the light or the position in the room change the way the viewer beholds the work. Teachers might even comment on the artist’s reference to a story known from the curriculum. But to what extent do we explore the meaning of the artwork and what the piece is intended to say, particularly regarding the lessons before us?

Romans referenced works of art as signa, for they were not frivolous bits of prettiness meant to delight the eyes and nothing more.1 These works were intended to convey a message and engage the viewer in conversation. This may be most readily seen in the great monuments to rulers such as the triumphal arch or the façade of an ancient temple. These speak to their power, might, and even their connection to the divine. However, the observer Pliny the Elder often uses the term signum in place of the word for a painting or statue even in reference to specific solitary images such as the Aphrodite of Knidos, one of the most famous statues from the ancient world. I would argue that we as teachers of the humanities would do well to learn from Pliny’s example. Let us take the pictures off the walls for more than a moment of time. Let us invite the statuary to stand at the class lectern. The discovery may take a little digging; for centuries and even millennia later that meaning can be lost on the viewer, as the conversation has long been quiet. And yet, if we can guide our students in finding bits of the dialogue once spoken, we can renew the conversation, and gaze at an intrinsic beauty—sometimes soft and gentle, but at other times fierce and furious. We may even find that our first impression of the artwork gives way to a deeper meaning of the textual studies before us.

Let us take the Laocoon Group as a case study for such an exercise. In the year A.D. 1506, the infamous serpents were drawn from the earth by a group of stone masons who were working on a site that later proved to be the ancient baths of Titus. The excavation halted to send for Italian sculptor Giuliano di San Gallo, who was found at breakfast along with Michelangelo. At this time in history, very few ancient sculptures had been found. The great Farnese Hercules and the lovely Venus de Milo both still slept under the earth. Thus, the pair of sculptors hastened to the site with great excitement. At first glance Michelangelo said, “That is the Laocoon of which Pliny speaks” (Goodyear, 222). In the first century A.D., Pliny the Elder had written his Historia Naturalis, a great work consisting of 37 books on various subjects of science from biology to geology to civil engineering. In a beautiful display of the natural relationship the ancients held between science and art, Pliny discusses the best examples of sculpture in his discourse on various types of stone. In the moment that Michelangelo beheld this statue group, he recalled Pliny’s words:

sicut in Laocoonte, qui est in Titi imperatoris domo, opus omnibus et picturae et statuariae artis praeferendum. ex uno lapide eum ac liberos draconumque mirabiles nexus de consilii sententia fecere summi artifices Hagesander et Polydorus et Athenodorus Rhodii. (Pliny, 36.37)2

Here Pliny reveals to us, as he did to Michelangelo, the location (the house of Titus), the subject matter (the death of Laocoon and his sons) and even the names and origin of the three sculptors themselves (Agesander, Polydoros and Athenodoros of Rhodes). What Pliny does not seem to reveal is the signum or meaning of the statue group. What was its purpose? What story does it have to tell? If we search the pages of history and literature, we may uncover the answers. Let us begin with the clue Pliny leaves regarding the three sculptors and their connection to the Isle of Rhodes.

What was its purpose? What story does it have to tell? If we search the pages of history and literature, we may uncover the answers.

For years scholars have debated the relationship of the three sculptors’ names. Nathan Badoud, professor at the University of Friborg, Switzerland, suggests that they are best called a group of artistic ambassadors. Rhodes was a tripartite city, a synecism from 408 B.C., which consisted of three communities known as Lalysos, Camiros, and Lindos. Rhodes chose these three sculptors, each an outstanding artisan from one of these three communities, to represent the synecism in presenting a diplomatic gift to the imperial family.3 The key to Badoud’s theory lies in Pliny’s descriptive phrase for the sculptors’ task, consilii sententia, a phrase found only once elsewhere in Latin, the Phocion of Cornelius Nepos.4 Both uses of this phrase by Pliny and Nepos align well with the Rhodian legal phrase, βουλᾶς γνώμαι (by order of the council).5 The phrase thus suggests that these three men were called upon by a city council for the purpose of collaborating on a single work that would represent the synecism of Rhodes. The occasion for this collaborative gift was the presence of Tiberius, who studied Rhetoric at Rhodes upon his return from Armenia in 20 B.C.6 It was appropriate that Rhodes respond generously to his presence and patronage, as the son-in-law of the emperor and potential heir, with an appropriate diplomatic gift. This theory fits within the tradition of Rhodes, which was known for offering conciliatory gifts of a similar nature to other men of significant importance. The Rhodians had once presented Alexander the Great with a garment crafted by Heikôn of Salamis. In 50 B.C. they gifted the Roman consul P. Lentulus a head crafted by Chares of Lindos, the famed sculptor of the Colossus of Rhodes and student of Lysippos (Badoud, 81).7

This gesture to Tiberius as a member of the imperial family was of particular importance given Rhodes’ standing with the new imperial dynasty. Rhodes had fallen from the good graces of Augustus when she sided with Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C., just a decade before. Generosity and excellence were required, and the Laocoon seems to have done its work; for it was not long afterward that the imperial family commissioned another work by this very same trio of sculptors known today as the Sperlonga group.8 The names of these same three sculptors—Hagesander and Polydorus and Athenodorus—appear on one of the most prominent of the sculptures at Sperlonga, a depiction of Scylla attacking the crew of Odysseus.9

Pliny the Elder may have indicated the purpose of the Laocoon Group in his words consilia sentii, but why might the Rhodesian sculptors have decided on the figure of Laocoon’s death for such a conciliatory gift? How might this scene from his story pay tribute to the Augustan dynasty? Here are questions worthy of class discussion! From the moment of its rediscovery in 1506, readers of the Aeneid have come to equate the statue with the tragic scene of the death of Laocoon and his sons in Book 1 of Vergil’s magnum opus. The poet writes that the priest Laocoon, distrusting the Greeks and their reputation for guile, had admonished the Trojans to destroy the ominous horse. Laocoon had cried out: timeo Danaos et dona ferentis (I fear Greeks even bearing gifts), as he hurled his spear into the belly of the dreaded horse (Aeneid 2.49-52). Several verses later, we learn that Laocoon was chosen by lot to serve as Neptune’s priest. While he performs his seemingly pious duties, a pair of ominous sea serpents attack him and his two sons:

. . . . illi agmine certo

Laocoonta petunt; et primum parva duorum

corpora natorum serpens amplexus uterque

implicat et miseros morsu depascitur artus;

post ipsum auxilio subeuntem ac tela ferentem

corripiunt spirisque ligant ingentibus; et iam

bis medium amplexi, bis collo squamea circum

terga dati superant capite et cervicibus altis.

ille simul manibus tendit divellere nodos

perfusus sanie vittas atroque veneno,

clamores simul horrendos ad sidera tollit

(Aeneid 2.212-222)

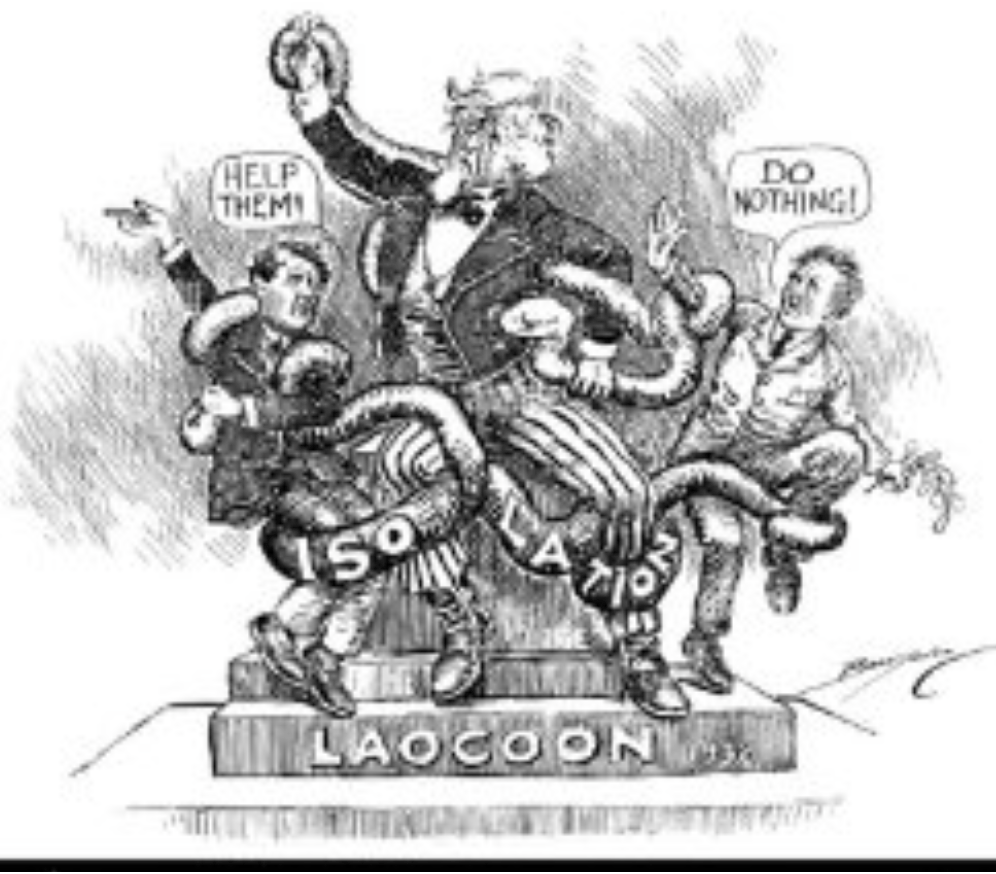

To the Trojans it appears as though the gods have silenced the priest in response to his own attack on the infamous wooden horse. Laocoon, therefore, is seen as a pious patriot who falls victim to the whimsy of the gods who have destined Troy for destruction; perhaps even a pawn within the divine politics at work on Mount Olympos. Indeed, this view of Laocoon’s death coupled with the famed sculpture group by a trio of Rhodesian sculptors has inspired many political cartoons in the modern era. Take for example the patriotic image of America’s Uncle Sam entangled by the schemes of political parties.

To the Trojans it appears as though the gods have silenced the priest in response to his own attack on the infamous wooden horse. Laocoon, therefore, is seen as a pious patriot who falls victim to the whimsy of the gods who have destined Troy for destruction; perhaps even a pawn within the divine politics at work on Mount Olympos. Indeed, this view of Laocoon’s death coupled with the famed sculpture group by a trio of Rhodesian sculptors has inspired many political cartoons in the modern era. Take for example the patriotic image of America’s Uncle Sam entangled by the schemes of political parties.

We as teachers would do well here to stop and ask our students, whether reading the poem in Latin or English, how Vergil’s description agrees with the statue and where the two descriptions (poetry and stone) seem to disagree. Certainly, there are similarities between Vergil’s poetic death scene and the Laocoon Group. The central figure of Laocoon is engulfed by the coils of snakes (spirisque ligant ingentibus) and his mouth, slightly agape, still raises silent shouts to the stars (clamores simul horrendos ad sidera tollit). The priest seems to grapple with the coils of one snake about his own head, though the head and neck of the serpent are not presently over the priest (superant capite et cervicibus altis). Apart from these similarities students may also find notable differences. In Vergil’s poem the serpents kill the sons of Laocoon first (primum parva duorum corpora natorum serpens amplexus). The two young boys are dying or even dead by the time their father reaches them. Laocoon must also leave his altar as he runs, weapon in hand, to aide them (post ipsum auxilio subeuntem ac tela ferentem / corripiunt). The marble image shows Laocoon himself on the altar. While one son seems to have succumbed to the snake’s death grip, the older boy is still very much alive—and just might escape. The sequence of the action and the location of the priest in the statue seem to depart from Vergil’s scene. Perhaps the class might dismiss these discrepancies as the employment of artistic license, either on the part of the poet or the sculptors, depending on which work came first. If our class discussion, therefore, wants to link these two works, the question of time is worth exploring.

Throughout the ages historians have assigned a wide range of dates to the Laocoon Group, from the fourth century B.C. to the first century A.D. The publication date of Pliny’s Historia Naturalis, which provides a terminus ante quem for the work of A.D. 79, does not reasonably allow us to consider a date later than this. If we agree with Badoud that the artists to whom Pliny ascribes the Laocoon Group are indeed those whose names are inscribed on the Scylla of Sperlonga, then this brings the date of the work in question closer to Vergil’s time. Samples taken from the statue of the Scylla in June 2010 date the marble to the Augustan era.10 The marble of the Scylla, a type known as Docimium marble, does not appear to be in use before 20 B.C., but becomes highly popular, even gains international renowned, after this date.11 This is the same year in which Tiberius himself is in Rhodes. The Laocoon, a single group, is most likely the work created first, as the diplomatic gift of Rhodes related to the patronage of Tiberius. The Sperlonga collection, consisting of a variety of sculpture groups of enormous size, would not have been a gift, but an imperial commission. This collection was sculpted and assembled sometime after the Laocoon Group at the imperial villa on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Thus, 20 B.C. becomes another possible terminus ante quem for the creation of the Laocoon Group.

Consider that Vergil died in September of 19 B.C., the following year, while still finishing his great epic. Augustus ensured his magnum opus would be published as soon as possible. This places the publication of the Aeneid around the end of 19 B.C. or into 18 B.C., after Tiberius’ time in Rhodes. It is possible that the sculptors gained an advanced glimpse of Vergil’s work, but not probable. It is equally unlikely that Vergil would have had opportunity to view the statue and consider it as inspiration for his scene. Nor was it necessary. The image of Laocoon and his sons entangled by serpents existed long before the age of Augustus.12 The literary source of inspiration for both lies elsewhere. Neither the tale of Laocoon nor the Trojan Horse appears in Homer’s war story. However, this tale does appear among the works credited to Euphorion, a Greek poet and favorite of Tiberius.13

The Laocoon was an extravagant piece of Hellenistic Baroque art, a style imbued with passion and fury.

Tiberius favored Greek myth and poetry. Suetonius records that the emperor found delight in conversation with men of learning on Greek myths and enjoyed assessing them on the various points of stories and origins:

Fecit et Graeca poemata imitatus Euphorionem et Rhianum et Parthenium, quibus poetis admodum delectatus scripta omnium et imagines publicis bibliothecis inter veteres et praecipuos auctores dedicavit; et ob hoc plerique eruditorum certatim ad eum multa de his ediderunt. Maxime tamen curavit notitiam historiae fabularis usque ad ineptias atque derisum; nam et grammaticos, quod genus hominum praecipue, ut diximus, appetebat, eius modi fere quaestionibus experiebatur: “Quae mater Hecubae, quod Achilli nomen inter virgines fuisset, quid Sirenes cantare sint solitae.”

(Suetonius, 3.70)

From Suetonius we learn that Tiberius himself loves Greek literature, to the extent that he himself seeks to compose in the style of Euphrion and others (Fecit et Graeca poemata imitatus Euphorionem). He includes Euphorion’s portrait and writings in the libraries (scripta omnium et imagines publicis bibliothecis). Finally, he loves to indulge in discussions exploring the mythological tales of these poems. What might better serve as a focal point for such discussion than a truly epic sculpture group? From Vitruvius’ discourse on the decorations of Roman villas we also know that scenes related to the Trojan war and its heroes were a popular style of decoration in dining areas in the first century B.C.14 The Laocoon was an extravagant piece of Hellenistic Baroque art, a style imbued with passion and fury. This was also the style of the Sperlonga group and the attic frieze of Tiberius’ arch in Orange.15 The style of the Laocoon Group, the subject matter, and even the poet Euphorion all fit the known tastes of Tiberius.

Euphorion’s poetry is lost to us, but his account of Laocoon’s story survives through a commentary on Vergil’s Aeneid written by Maurus Servius Honoratus, A.D. 1471. Servius tells us that Euphorion served as a source for Vergil in both his Georgics and the Aeneid. As a highly favored Greek poet, his work was familiar to the Rhodesian sculptors. As Servius’ commentary reaches the lines of Laocoon’s death scene in Book Two of the Aeneid, the commentator makes note of Euphorion’s prior work:

ut Euphorion dicit, post adventum Graecorum sacerdos Neptuni lapidibus occisus est, quia non sacrificiis eorum vetavit adventum. postea abscedentibus Graecis cum vellent sacrificare Neptuno, Laocoon Thymbraei Apollinis sacerdos sorte ductus est, ut solet fieri cum deest sacerdos certus. hic piaculum commiserat ante simulacrum numinis cum Antiopa sua uxore coeundo, et ob hoc immissis draconibus cum suis filiis interemptus est. historia quidem hoc habet: sed poeta interpretatur ad Troianorum excusationem, qui hoc ignorantes decepti sunt.

(Servius, Commentarius in Vergilii Aeneida 2.201)

Now we have a new point of classroom discussion: in what way might Euphorion illuminate our understanding of the sculpture? Does he address the obscurities left by Vergil’s scene? According to Euphorion, Laocoon violated the commands of celibacy imposed by Apollo, desecrating the altar of the god (hic piaculum commiserat ante simulacrum numinis). Servius cites Euphorion with the Latin word piaculum, which denotes a wicked crime that demands expiation.16 Thus, in payment for his wickedness, Apollo’s snakes attacked Laocoon along with his sons while at the altar (cum suis filiis interemptus est). Moreover, note that Servius states that this is the tale of Laocoon held by history (historia quidem hoc habet), meaning it predated even Euphorion. In fact, the Greek poet Arktinos, who writes nearly a half-millennium before Euphorion, also relates this same tale and further claims that Laocoon’s elder son escaped the serpents’ attack.17 All of this—the simultaneous attack on Laocoon and his sons, the position of the altar, and the elder son’s escape—are absent from Vergil’s poem, but present in the work of the Rhodesian sculptors. Furthermore, Vergil is known to take ancient myths and adapt them for the purposes of his own narrative.18 Servius suggests that Vergil knows this version held by history, but instead interprets the scene from the viewpoint of Aeneas and the Trojans (poeta interpretatur ad Troianorum excusationem) who would not have known of Laocoon’s piaculum (qui hoc ignorantes decepti sunt). Perhaps Vergil expected his readers would have known the Greek story told by Euphorion and Arktinos as well.

From the view of Troy and Aeneas in Vergil’s poem, the gods killed Laocoon to ensure the defeat of Troy. His was a tragic and perhaps patriotic sacrifice, not a punishment for impiety and sacrilege.19 When Euphorion’s tale is considered, a different meaning emerges from the stone. The death of Laocoon and his son was the expiation of a wicked sin against the god Apollo. Furthermore, Servius’ commentary continues to remind his readers that it was by the hands of Apollo and Neptune, upon a fixed agreement with King Laomedon of Troy, that the impregnable walls of Troy rose from the earth. King Laomedon reneged on the payment. Thus, Apollo had grievance not only against the priest, but also against the city of Troy herself.20 This changes the signum of the piece as our students might behold it. We must now consider with them how such a piece, viewed in this light, pays tribute to the Augustan dynasty.

Exploring the signum of a piece such as the Laocoon Group trains our students to see beyond the surface of a work of art just as we would have them look beyond the cover of a book to judge each on the deeper meaning of its content.

Less than a decade before Tiberius’ visit to Rhodes and the creation of the Laocoon Group, Rhodes had sided with Mark Antony, and against Augustus, at the Battle of Actium. Mark Antony had once served as the right-hand of Julius Caesar, adoptive father of Augustus. Mark Antony had fought alongside Augustus to take vengeance on Caesar’s assassins, most notably Brutus and Cassius. Later as they divided the empire between them, Mark Antony declared himself allied with Augustus, both in terms of politics and family as he married Octavia, Augustus’ beloved sister. However, Mark Antony betrayed Octavia, Augustus, and Rome when he chose to call himself husband to an Egyptian queen and build her empire. The final confrontation between these two Roman leaders came off the shores of Actium where a temple of Apollo stood. Mark Antony lost. Not long afterwards he and his Egyptian queen lay dead. Rhodes found herself on the side of the loser in this fight, now known for wicked impiety against Augustus and against Rome.

Beyond the typical Trojan War genre for decoration, beyond the allusions to myth and poetry, the image of Laocoon’s fate captured by the three Rhodesian sculptors reminds viewers of a real story, with a real warning. The Laocoon Group may convey a conciliatory message, even an apology, after Rhodes had fought against Augustus at Actium. The image of Laocoon is the image of Mark Antony, who betrayed both Augustus and Rome through an impious attachment to Cleopatra.21 One of his sons paid the price for his father’s betrayal; others of his children were spared.22 This statue then bears a signum to its audience: the impiety of Mark Antony (Laocoon) against Augustus (Apollo, the emperor’s patron deity) is justly met by divine vengeance.23

Exploring the signum of a piece such as the Laocoon Group trains our students to see beyond the surface of a work of art just as we would have them look beyond the cover of a book to judge each on the deeper meaning of its content. Each one informs the understanding of the other. Such lessons take time, but the greatest treasures are rarely found with ease. Even the incorporation of a very few select studies each year trains the eyes and minds of our students. The students not only gain a deeper understanding of a particular work of art, but the context of art within classical civilization and the relationship between artist and patron. They have explored Vergil’s poetry more deeply in searching out just a fraction of his source material, realizing that he borrowed from a poetic tradition wider than Homer. Of course, this means that we as teachers must first make such discoveries so we can guide our students. That may seem a daunting task. Thankfully, we are not meant to take on such journeys alone. My own journey towards the exploration of relationships between written and material evidence came through discussions with an artist very dear to me, my sister. She inquired of me who might be the characters or what might be the symbols in a work of art. I would ask her what her trained eye saw in a work that mine were yet too dull to see. Together we sharpened each other’s senses and in so doing found a more complete understanding of a piece we had before each seen only in part. This led to each of us researching further on our own so we could bring more to the conversation. This can be and ought to be the relationship that we as teachers of the humanities have with our co-laborers in the arts. As teachers we are not meant to be masters of all knowledge, but fellow sojourners along the path of life-long learning. We just happen to be a few steps farther along than our students. So let them see us engage with each other in the exploration; let them see us model the conversation.

So often, particularly in the grammar school years, the art teachers fill their lesson plans with work that complements the humanities classroom. This is certainly true of my dear friend and colleague of many years, Robin McLaurin. An accomplished artist herself, she guides our students in studying Greek pottery, the illuminated manuscripts of the Medieval period, the masters of the Renaissance (Michelangelo, Raphael, Botticelli) and the great works of the modern period (Dali, Matisse, Picaso). Each lesson carefully aligns with the period of history and literature studied in those years. She takes great care to curate lessons and student exhibits that demonstrate this connection. She inspired me not only to make use of the foundation she has laid with our students, but to return the favor. One step at a time, I began to build art-literature lessons such as the Laocoon.24 I modeled the exploration, then I challenged my students to make their own.

Slowly they walk through museums and archaeological sites with eyes to see before them the various signa created by artists, men and women who had something to say in response to the literature and history that shaped their world. They can then take up the discussion with each other and with their teachers not only remarking on the marvelous skill the artist exhibited, but what signum the art expresses.

My humanities class must choose a work of art from a select list of works they will see when I take them to Italy in their senior year. Their term paper must discuss the chosen work in light of classical literature. They are now in the position of the discoverer, seeking the signa of the artist; and I have the pure joy of learning from them. I am delighted to share two such papers in Commonplace. Each one was inspired by a work that captivated the attention of the author while on her senior trip to Italy this spring.

Truly, nowhere is the fruit of such integration between the arts and humanities better tasted than when the students visit great masterpieces around the world. They meet paintings and monuments as if they were old school friends and classmates. Slowly they walk through museums and archaeological sites with eyes to see before them the various signa created by artists, men and women who had something to say in response to the literature and history that shaped their world. They can then take up the discussion with each other and with their teachers not only remarking on the marvelous skill the artist exhibited, but what signum the art expresses. What of the proud obelisk with the detailed figures carved in ancient stone? What muse inspired the figures in Botticelli’s paintings? What signa do such works on stone and canvas convey? We would do well to attune our students’ eyes to hear the language of the artist and to awaken the conversation begun centuries before. Hopefully, one fine day these students will each stand before the Laocoon Group in the Vatican Museum. In that moment, in the presence of the work itself, they may also utter the words, “so this is the Laocoon of which Pliny speaks” and the conversation begins anew.

Karen T. Moore has served as the Classical Languages Chair at Grace Academy of Georgetown, TX, since 2002. During her years at Grace Academy she has taught Latin, Greek, Ancient Humanities, and assisted with curriculum development. Karen is also the author of several Latin books including the Libellus de Historia series, the Latin Alive series (Classical Academic Press) and Hancus ille Vaccanis (Logos Press). Most recently, she has developed an online course in Classical Art & Archaeology with ClassicalU, which discusses the material in this article among other works of art. Karen is also an adjunct professor in Classics with Houston Christian University and a board member with the ACCS Institute for Classical Languages. Karen holds a B.A. in Classics from the University of Texas at Austin and an MSc with Distinction in Classical Art & Archaeology from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Karen and her husband Bryan are the proud parents of three Grace Academy Alumni. When not reading Latin literature, Karen can be found working in her garden, hiking with her family, or leading her students in adventures across Italy.

Footnotes

1. Pliny the Elder often uses the word signum (sign) for statues and paintings in his Historia Naturalis. See Book 36 chapter 6 of this work where the author uses the term specifically for the Venus of Cnidus (Aphrodite of Knidos) and then generally for other statues.

2. See “Old Voices” for the English translations of all Latin passages in this article.

3. For a thorough examination of the relationship of these three sculptors, their work, and the communities they represent see Badoud (2019), 75-77.

4. Cornelius Nepos, Phocion 3.

5. Blinkenberg (1906), 47-54, 75-82; Badoud (2019), 72.

6. Plut. Brutus 2. 96 Suet. Tib. 9, 1; Cass. Dio 54, 9, 4–5.

7. See Plutarch’s Life of Alexander 32.6 and Pliny’s Natural History 34.18, for an account of these gifts.

8. The Sperlonga Group is a collection of life size and larger than life statue groups that were once on display in a dining cavern adjacent to an imperial villa on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is believed the imperial family commissioned this group during the reign of Augustus or Tiberius. For a more detailed explanation of the Laocoon as a diplomatic gift from the consilii sententia of Rhodes and its relationship to the Sperlonga group see Badoud (2019).

9. The question of the connection between the sculptors of Laocoon, recorded by Pliny, and the sculptors’ names inscribed on the Scylla has been debated since their discovery. To learn more about the compelling evidence that these are indeed the same three men see Badoud (2019), Bruno et al. (2015) and Stewart (1977).

10. Bruno et al. (2015), 10-16.

11. Bruno et al. (2015), 382; Fant (1989), 6-9.

12. One such example is the engraved image of Laocoon and sons on a gem dated to the fourth century B.C., now on display at the British Museum.

(A. Furtwiangler, Die Antiken Gemmen i (i9oo), pl. 64 no. 30; III, 205; Richter, The Engraved Gems of the Greeks and Etruscans (I968), 2o8, no.

851).

13. Euphorion of Chalcis, a highly regarded Greek poet and grammarian of the third century B.C.

14. Vitruvius, De Architectura 7.5.2.

15. Stewart (1977), 83. The Triumphal Arch near Orange, France, contains a dedicatory inscription to the Emperor Tiberius, dated 27 B.C. The arch is adorned with sculptural reliefs depicting naval battles, spoils of war, and battles between Romans and Gauls in graphic detail. The Sperlonga Group references mythological stories told in both the Odyssey and the Aeneid. See also footnote 8.

16. Vergil uses this same word piacula in Aeneid 6.569 as Aeneas describes the expiation demanded from the wicked in Tartarus, an idea carried forth by Dante in his Inferno.

17. Stewart (1977), 82-83. Arktinos is believed to have written poetry c.775 B.C., five hundred years before Euphorion. The work of both poets is lost and survives only in the words of others who admired them and carried forth portions of their work.

18. Such is the case with his account of the affair between Aeneas and Dido, which earlier myths claim involved not the Carthaginian queen, but her sister Anna.

19. Badoud (2019), 81-3.

20. Ovid retells the story of Troy’s walls in Book 11 of his Metamorphoses.

21. Badoud (2019), 83

22. See Suetonius 2.17.

23. Laocoon is an apt image as Mark Antony violated his marriage to Octavia with Cleopatra. Augustus favored the god Apollo, building a temple to the sun god next to his home on the Palatine Hill. According to Suetonius, legend held that Apollo was the father of Augustus after appearing to his mother Atia in the form of a serpent (Div Aug, 94).

24. As a resource for those who would like to embark on such discoveries, please see my course on Classical Art & Archaeology with ClassicalU where I explore the history and meaning of classical art in light of literature.