What are the Liberal Arts?

Glossary

of Terms

The Liberal Arts:

The seven liberal arts are skills that free a person to learn for themselves, direct themselves, and lead others well. They cultivate one’s reasoning skills and provide one with the tools of learning through seven arts divided into the trivium and the quadrivium.

The term “liberal” has some misleading connotations, but classically understood, the liberal arts are those habits and skilled arts practiced by a “free” person, who needs no taskmaster but is able to direct himself to the right activity and lead others. Once, the term art simply meant that skill which produced something new. On one hand, a person can build a rocking chair by imitating or copying someone else, but mere imitation is not art. On the other hand, if he had read many books about building rocking chairs but did not build them himself, his knowledge would be considered “science” rather than art. Science in this sense comes from the Latin word scientia, meaning knowledge. Rather, an art is a practiced skill or habit oriented towards the production of a thing. In this case, the liberal arts are oriented towards the production of a free and therefore virtuous soul. This kind of education extends beyond forming a mind that can think and reason. Someone may learn a skill through imitation and knowledge, but in order for it to become an “art,” he needs to add his own mind and imagination to the creative process.

While fine arts produce beautiful music and art, and mechanical arts produce solid rocking chairs and car engines, liberal arts make right thoughts, words, and human virtue. They train the human mind in logic, language, and mathematics, giving one the tools to gain knowledge and incarnate the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. They are called “liberal,” because they make for free-thinking people, people who don’t need others to direct them but can direct themselves, people who can lead others.

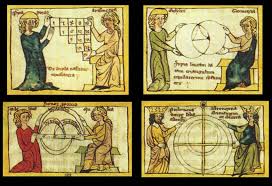

During the middle ages writers like Cassiodorus and Isidore of Seville organized the liberal arts, identifying seven arts divided into two groups: the trivium and the quadrivium. The arts of the trivium and quadrivium existed in the ancient world and were codified in the early medieval era, but it was not until the middle ages that writers like Cassiodorus combined them under the heading of liberal arts.

These seven [the ancients] considered so to excel all the rest in usefulness that anyone who had been thoroughly schooled in them might afterward come to a knowledge of the others by his own inquiry and effort rather than by listening to a teacher.

The Trivium:

The three arts of language: grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium are the liberal arts of language. We must not forget that, according to ancient and medieval understanding, the ability to use language goes hand in hand with the ability to reason and think; his ability to reason and speak sets man apart from animals. The curriculum of the trivium comprises the arts of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, the instruction of which can happen in several ways.

The three arts in the trivium are disciplines, skills, or habits of mind. Grammar involves learning the fundamentals of a language–letters, words, syntax, as well as etymology, interpretation, and meaning. In the middle ages and early modern era this language was Latin, which, because it was the language of the monastery, fading Roman Empire, and the church, was the universal language of communication and scholarship in the West well into the modern era. Logic (also called Dialectic) trains a person in proper reasoning so they identify true from false, develop new conclusions from prior knowledge, gain clarity in argument, and provide refutation of error. This is why many classical schools embrace Socratic discussion. Rhetoric teaches a student to discover all the available means of persuasion. This includes not only logical argument, but sound character and judgment, as well as emotional appeal. The study of rhetoric is not primarily about results but about forming what Cicero called “the good man speaking well.” Classical schools teach these three arts because they are necessary to linguistic skill and thus our ability to think and communicate with one another about the true, good, and beautiful.

Different arts of the trivium received special emphasis or hierarchy throughout history. Cicero, for instance, placed the art of rhetoric as most important for statesmen and senators. For those in late antiquity who focused on the interpretation of Scripture, such as St. Augustine, the art of grammar was most important. But today many classical schools organize their grade levels in such a way as to prioritize and focus on one of the liberal arts. Many schools, for example, tend to follow the insights proposed by Dorothy Sayers in her essay, “The Lost Tools of Learning,” where greater attention is given to that liberal art that most appropriately fits with the development of the child (i.e. grammar in grades K-6, logic in grades 7-9, and rhetoric as the capstone in grades 9-12). Such an arrangement is not meant to undermine the importance of any other art but only to capitalize on the way children naturally mature.

The foundations of education are found in grammar. One must learn to read and speak before they can proceed to further instruction. 13-14 year olds are developing their ability to think in abstractions or consider the logical coherence of arguments, and so it is fitting to teach them the rules of formal logic as well as common informal arguments and fallacies. Older students who have been formed by a classical education are ready to give more attention to the art of persuasion, considering all three rhetorical appeals. This art must be practiced through copious public speaking, not merely writing. It is good to remember that the most persuasive appeal is ethos, or personal character. Students who have not been habituated to virtue will not be persuasive, no matter how logical their arguments. Nevertheless, while grammar remains fundamental and prior to the other arts, schools may choose to teach rudiments of rhetoric prior to formal logic.

The Quadrivium:

The four arts of mathematics or number: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music.

The Quadrivium, in order: Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy, and Music.

The quadrivium involves mathematics: reasoning with numbers and quantities. The four arts that the medievals categorized in the quadrivium were arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. Today, arithmetic and geometry are considered mathematical, although astronomy and music might seem out of place. The classical art of arithmetic dealt less in rote computation than in finding number patterns and number theory. Geometry, too, was less about plugging in the proper equation than about understanding magnitudes and doing proofs to understand and deduce equations for oneself. The ancients and medievals considered astronomy a subject of the same sort, because it involved meticulous observation and calculation to predict the movements of the stars. Music as math may sound foreign to us today, but the Greeks believed music was what numbers did in space and time because harmony, the key to music, deals in proportions.

Today, we tend to think of math primarily as a practical tool, but early Greek mathematicians like Pythagoras thought more highly of mathematics, believing it offered theoretical keys to understanding the world. Because the medievals and ancients thought of mathematics abstractly and theoretically, they learned it by figuring out for themselves how equations worked. The quadrivium was considered a liberal art because it was an exercise in logic, reasoning, and thinking, rather than in rote imitation.

“The study of arithmetic is endowed with much praise, since the Lord, maker of things, arranged the universe by number, weight and measure…. Although we can call all teaching theoretical, [the word ‘theoretical’] applies particularly to mathematics because of its excellence.”

– Cassiodorus, Institutes of Divine and Secular Learning, Book II. 3-4